Last updated 2022-12-03.

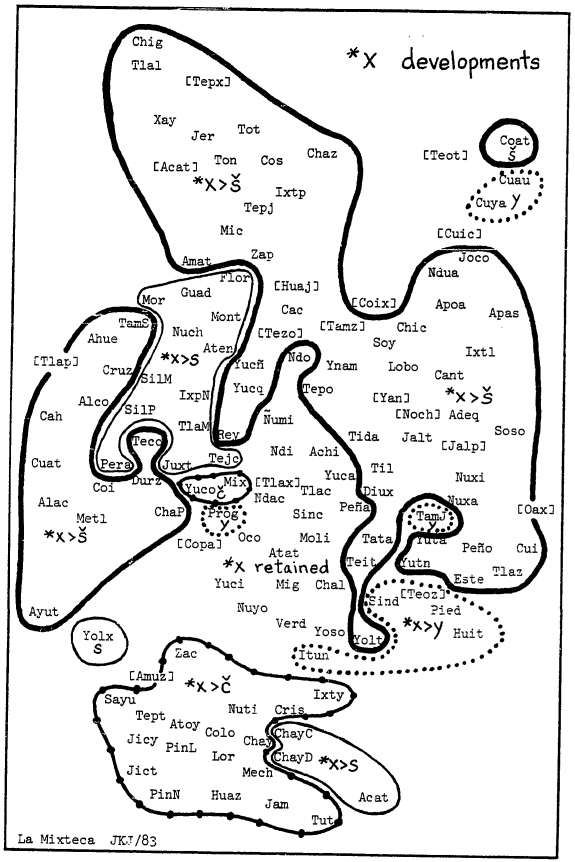

Previous reconstructions of Proto-Mixtec included a back fricative, labelled *x by Josserand (1983) and *h by Mak and Longacre (1960). I believe this segment is better reconstructed as a coronal affricate, *t͡ʃ.

Reconstructing this segment as *x in Proto-Mixtec would require some varieties of Mixtec to have undergone a change of *x → t͡ʃ. This seems intuitively unlikely: the fortition of fricatives to affricates, and the unconditioned change of POA from velar (or glottal!) to coronal, are both rare developments, and this kind of change is not to my knowledge attested in any other language. Yet, this interpretation would require this unlikely change to have occurred not once, but twice, in two non-contiguous areas within Mixtec (San Juan Mixtepec and the Costa region).

In contrast, the retention of *x as x is found only in one contiguous region (the Western Alta region). Most varieties of Mixtec reflect *x as a coronal fricative s or ʃ.

If Proto-Mixtec *x is instead reconstructed as *t͡ʃ, these reflexes can be explained in a simpler and more plausible way:

This interpretation repositions the Western Alta region in relation to its neighbors: rather than being the sole conservative region surrounded by innovators, it participated in the same *t͡ʃ → ʃ change that many of its neighbors did, and followed this with an innovation of its own.

Proto-Mixtec *x is found almost exlusively before the front vowels *i and *e. The only example of *x before a non-front vowel in Josserand’s reconstructions is *xɨtɨ ‘guts’.

The distribution of Proto-Mixtec *k is the inverse of *x: it occurs almost exclusively before non-front vowels. Josserand’s reconstructions contain only four exceptions: *kejiʔ ‘go out’, *kini ‘ugly’, *kixi ‘will come’, and *xekĩ ‘lay (egg)’.

It is possible that *xɨtɨ may have originally been *xitɨ, and that those words reconstructed with *ki may have originally had *kɨ instead. Some limited evidence for this is presented below. If this is accepted, it would leave *kejiʔ as the sole example of *k before a front vowel.

| Proto-Mixtec | *xɨtɨ | *kejiʔ | *kini | *kixi | *xekĩ | (Josserand 1983) |

| colonial Eastern Alta | site | cai | quene | quesi | saque | (Alvarado 1593, as written) |

| colonial Eastern Alta |

ʂitɨ | kai | kɨnɨ̃ | kɨʂi | ʂakɨ̃ | (reconstructed pronunciation) |

| Santiago Nuyoo | itɨʔ | kihi | (h)jakɨ̃ʔ | (Harris & Harris 2006) |

Thus it appears that Proto-Mixtec *x and *k were at one point in complementary distribution, and that *x originated as an allophone of *k, conditioned by a following front vowel.

When comparing Mixtec words to their equivalents in related languages, Mixtec *x and *k often correspond to the same segments.

In the following table, the Proto-Mixtec reconstructions are from Josserand (1983), except those in [square brackets] which I have reconstructed. Cuicatec is represented by Santa María Pápalo (Anderson & Concepción 1983), Triqui by San Juan Copala (Hollenbach 2022), and Amuzgo by San Pedro Amuzgos (Stewart & Stewart 2000). Not all of the words cited are definitely cognate. In some words, the first syllable may differ for morphological rather than phonological reasons.

| Proto- Mixtec |

Cuicatec | Triqui | Amuzgo | |

| ‘yesterday’ | *iku | iku | kiː | |

| ‘squash’ | *jɨkɨ̃ʔ | juku | kãː | t͡skẽ |

| ‘brush’ | *juku | jiku | koh | t͡sko |

| ‘hill’ | *jukuʔ | jiku | kih | |

| ‘pine needle’ | *juxeʔ | jjaka | kaʔ | |

| ‘cornmeal’ | *juxẽʔ | jat͡ʃi | kũh | t͡skẽ |

| ‘cotton’ | *katiʔ | kut͡ʃi | kat͡ʃih | |

| ‘big’ | *kaʔnuʔ | kaʔnuʔ | ||

| ‘will come’ ‘is coming’ |

*kixi *wexi |

t͡ʃi jit͡ʃi |

||

| ‘animal’ | *kɨtɨʔ | iti | ||

| ‘day’ | *kɨwɨʔ | guβi | gʷiː | ʃue |

| ‘snake’ | *kooʔ | ku | (ʃ-)kʷaː | |

| ‘comb’ | *kuka | kaka | kit͡siʔ | ʃkaʔ |

| ‘chachalaca’ | *laxẽʔ | laka | ||

| ‘glue’ | *ⁿdeka | nakah | ||

| ‘grind’ | *ⁿdikoʔ | jigu | ||

| ‘sandal’ | *ⁿdixẽʔ | ⁿdɑku | kãh | t͡skõ |

| ‘horn’ | *ⁿdɨkɨʔ | kuː | ||

| ‘vomits’ | *ⁿduxẽʔ | ⁿdat͡ʃi | ||

| ‘nephew’ | [*saxĩ] | ðaku | (ʃ-)tikũʔ | |

| ‘resin’ | [*suxe] | ðat͡ʃa | skiː | ska |

| ‘belly’ | [*tixi] | rke | ||

| ‘seven’ | *uxe | ⁿdat͡ʃa | t͡ʃih | ⁿtʲkeʔ |

| ‘ten’ | *uxi | ⁿdit͡ʃi | t͡ʃiʔ | nki |

| ‘lay (egg)’ | *xekĩ | iʔku | ikẽ | |

| ‘box’ | *xetũʔ | ʈ͡ʂũː | stõ | |

| ‘eat’ | *xexiʔ | jit͡ʃi | t͡ʃa | iki |

| ‘foot’ | *xeʔe | kɑʔɑ | t͡ʃeʔe | ʃʔe |

| ‘griddle’ | *xijoʔ | t͡ʃa | ʃoː | ʃo(-t͡ʃiʔ) |

| ‘mushroom’ | [*xiʔjɨʔ] | geʔe | ||

| ‘guts’ | *xɨtɨ | gete |

Mixtec *k may correspond to Cuicatec k (8 examples), g (2), or zero (1); Mixtec *x may correspond to Cuicatec t͡ʃ (9 examples), k (5), g (2), j (1), or zero (1).

Triqui often loses initial consonants. In cases where the consonant survives, Mixtec *k may correspond to Triqui k (9 examples), kʷ (1), gʷ (1), or t͡s (1); Mixtec *x may correspond to Triqui k (6 examples), t͡ʃ (4), or ʃ (1).

This means, at least based on the data presented here, that Cuicatec t͡ʃ and Triqui t͡ʃ consistently correspond to Mixtec *x, but the reverse is not true. Furthermore, Cuicatec t͡ʃ and Triqui t͡ʃ do not necessarily correspond to one another.

Amuzgo presents the simplest pattern: Mixtec *k and *x both correspond to Amuzgo k medially, and to Amuzgo ʃ initially (or in one case, s).

I believe the best interpretation of this data is that the common ancestor of these languages had a single *k phoneme; that Mixtec, Cuicatec and Triqui all underwent a change of *k → t͡ʃ, but did so separately, affecting different words in each language; and that in Proto-Mixtec, the *t͡ʃ resulting from this change is what has previously been reconstructed as *x.

Alvarado, Francisco. (1593) Vocabulario en lengua misteca. Mexico: Pedro Balli.

Anderson, E. Richard, and Hilario Concepción Roque. (1983) Diccionario cuicateco: Español - cuicateco, cuicateco - español, México, D.F.: Instituto Lingüístico de Verano. Available online at https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/10945.

Harris, Larry R., and Mary Harris. (2006) Phonology of Santiago Nuyoo Mixtec. Digital draft manuscript. Available online at https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/56286.

Hollenbach, Barbara E. (2022) Diccionario triqui–español y español–triqui: Triqui de San Juan Copala. Preliminary version. Available online at https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/79578-0.

Josserand, Judy Kathryn. (1983) Mixtec dialect history. Ph.D. dissertation, Tulane University.

Mak, Cornelia, and Robert Longacre. (1960) Proto-Mixtec phonology. International Journal of American Linguistics, 26 (1): 23–40. DOI: 10.1086/464551.

Stewart, Cloyd, and Ruth D. Stewart. (2000) Diccionario amuzgo de San Pedro Amuzgos, Oaxaca. Instituto Lingüístico de Verano, A.C. Available online at https://www.sil.org/resources/archives/10968.